Expert WWI scale model or beginner’s nightmare? This laser-cut kit delivers precision parts but demands serious skills—and patience.

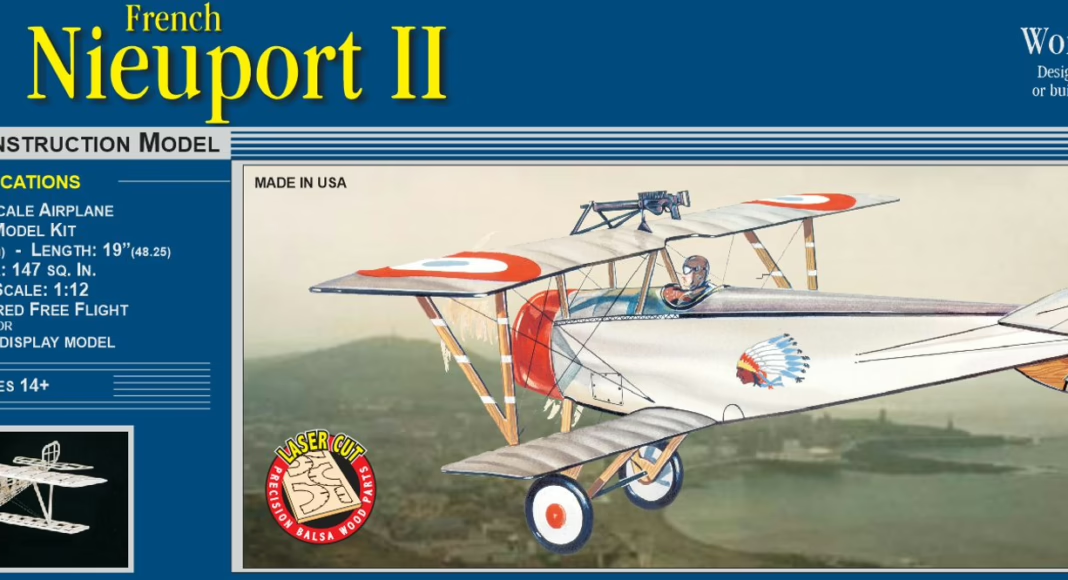

Walk into any hobby shop and you’ll see Guillow’s iconic boxes lining the shelves. The Nieuport 11 “Bébé” (Kit #203) sits among them, its wrapper promising a piece of aviation history: the legendary French World War I fighter flown by the Lafayette Escadrille. At 24 inches of wingspan and marketed for “Ages 14+,” it looks approachable enough. But don’t let that fool you.

This is where I need to be straight with you: if you’re a first-time builder looking for a weekend project that’ll fly beautifully on rubber power, walk past this box. If you’re an expert seeking a challenging R/C conversion platform or a patient craftsman who loves the stick-and-tissue building process, this might be exactly what you’ve been searching for.

The Guillow’s Nieuport 11 is a study in contradictions—modern laser-cut precision trapped in a decades-old design philosophy that prioritizes scale accuracy over flight performance. After reviewing extensive builder logs from modelers who’ve tackled this kit over multiple years, I’ve found that understanding who this plane is really for makes all the difference between frustration and satisfaction.

What You’re Actually Getting

The Nieuport 11 was originally designed for racing before being pressed into combat service during World War I. This small, maneuverable biplane earned its affectionate nickname “Bébé” (baby) for its diminutive size. Guillow’s Kit #203 attempts to capture that historical charm in a 1/12 scale model (though you’ll see some retailers incorrectly listing it as 1/14—the manufacturer’s own website confirms 1/12).

The kit markets itself as a three-in-one proposition: build it as a static display, fly it rubber-powered, or power it with a .020 nitro engine. But the community of experienced builders has discovered a fourth option that’s become the kit’s primary appeal—electric R/C conversion. That unintended versatility tells you everything about what this kit really is: not a beginner’s flier, but an expert’s challenge.

When you open the box, you’ll find laser-cut balsa wood sheets, white tissue covering, two decal sheets, plastic detail parts (radial engine, machine gun, pilot figure, 2-inch wheels, nose cowl, and propeller), a steel control rod, rubber thread for the motor, and both an illustrated instruction sheet and full-size plan. On paper, it’s comprehensive. In practice, those materials set up a conflict that defines the entire building experience.

The Laser-Cut Revolution

The single most important upgrade Guillow’s made to this classic kit was switching to laser-cut balsa parts. Builder after builder praises this precision. One experienced modeler reported being “amazed at how everything fit so precisely,” noting the build “went together so nice it was hard to put down.” Another stated flatly: “Laser cut high quality balsa is great! Fit of parts is awesome.”

This precision represents a quantum leap over the older die-cut versions, where parts sometimes required significant tweaking. The laser cutting ensures that when you’re assembling the complex “half-shell” fuselage—more on that in a moment—the parts actually align where they’re supposed to. For a challenging build, that’s not a luxury; it’s essential.

But here’s the first major contradiction: while the cutting is precise, the wood itself is consistently described as “heavy.” This matters enormously because in the world of rubber-powered free flight, weight is the enemy. The denser balsa stock, possibly selected for robustness or ease of cutting, creates a finished model that fights against its intended purpose.

The Half-Shell Challenge

The Nieuport 11 doesn’t use a simple box fuselage that you’ll find in easier kits. Instead, it employs what builders call a “half-shell” or “semi-monocoque” construction method. You start with a center keel (top and bottom), glue half-sized frames to this central structure, then add a side keel that slots into those frames, locking one side together. Then you repeat the process on the other side.

Experienced builders call this approach “unusual” and “kinda clever” for forming the rounded fuselage shape that’s true to the original aircraft. But free-flight experts are less charitable, noting that this method “automatically involves far more wood than what is needed.” Every extra strip of balsa adds weight—weight that accumulates in all the wrong places.

That brings us to the kit’s fundamental design flaw.

The “Short Nose” Problem: Understanding the Core Challenge

Every single experienced builder who’s documented their work with this kit mentions the same critical issue: it’s “really tail heavy.” This isn’t a minor trim problem you can fix with a few adjustments. It’s baked into the design.

The historical Nieuport 11 had a rotary engine mounted in the nose—a heavy piece of machinery that naturally balanced the airframe. Guillow’s scale reproduction captures that short nose accurately, but when you’re not mounting a real rotary engine up front, you’re left with a structural problem. The “half-shell” construction method concentrates wood—and therefore weight—behind the wings. The result is an aircraft that wants to flip onto its back.

For rubber-powered free flight, this creates a cascading series of problems. Builders report needing “a lot of clay” or lead weight packed into the nose just to achieve neutral balance. But that added nose weight makes the plane heavier still, requiring more power to fly, which means more rubber, which adds more weight. It’s a vicious cycle that typically ends with a model that’s “way too heavy” and “hard to get flying.”

One experienced free-flight modeler put it bluntly: competitors would be “far, far better off with a built up stick box fuselage” from a performance-oriented manufacturer. The Nieuport 11’s scale fidelity comes at the direct expense of flight performance.

The R/C Conversion Reality

Here’s where the kit finds its true calling—and where things get interesting for a specific type of builder.

The 24-inch wingspan and 147 square inch wing area make the Nieuport 11 large enough to accommodate modern micro R/C equipment. Early adopters looked at the plans and realized that “RC/electric seems very possible.” They were right, but “possible” doesn’t mean “easy.”

Successful R/C conversions require solving that same tail-heavy problem, but with different tools. Builders must place every component—motor, battery, ESC, receiver, servos—as far forward as possible. One successful converter detailed his solution: battery mounted “vertically directly behind the firewall,” radio gear “right behind that,” with all equipment “forward of the lower wing leading edge.”

The center of gravity challenge is severe. Builders recommend setting the CG at 10mm aft of the bottom wing’s leading edge. One modeler tried 15mm aft and reported it was “almost uncontrollable.” That’s a 5mm margin for error on a 19-inch long aircraft—virtually no room for mistakes.

The wing incidence (decalage) also needs re-engineering. The kit plans are optimized for free flight, not R/C. Experienced converters recommend setting the top wing to +2 degrees positive incidence and the bottom wing to 0 degrees (neutral), rather than following the kit’s instructions.

Control surface challenges add another layer of complexity. The low wing area (147 square inches) and the target all-up weight of 7 ounces or less mean this is a high wing loading aircraft that stalls easily. For a three-channel setup without ailerons, one builder found it “will not turn well” and recommended engineering a “full flying rudder” to compensate.

Getting to that 7-ounce target requires aggressive weight reduction: scalloping the fuselage, using ultra-lightweight covering material, and carefully selecting the lightest possible electronics. Some builders replace the kit’s heavy tail wood entirely. It’s expert-level work, no question.

Scale Detail: Basic Starting Point or Replacement Candidate?

The vacuum-formed plastic parts sheet includes a cowl, radial engine facade, pilot figure, and machine gun. These are functional but basic. One builder described the “white plastic doesn’t look very inviting,” hoping that “with some work, glue, and a lot of paint” they might “end up looking OK.”

For serious scale builders, these parts serve as templates rather than final components. Builders looking for museum-quality results immediately turn to aftermarket solutions like Williams Brothers cylinder kits, or scratch-build their own detailed interiors, valve stems, and control linkages. The kit provides the framework for scale accuracy, but achieving truly impressive detail requires supplementing or replacing most of the included plastic components.

If you’re building for display, plan your budget accordingly. The kit gives you the structure, but the details are up to you.

Pros & Cons

Pros

Precision Laser-Cut Parts: The fit of components is exceptional, eliminating the frustration of misaligned parts and making the complex assembly process significantly more manageable. This is the kit’s standout modern feature.

Iconic Subject with Rich History: The Nieuport 11 is a “magnificent war bird” with genuine historical significance—the fighter of the Lafayette Escadrille. It’s instantly recognizable to aviation enthusiasts and makes a striking display piece.

Excellent R/C Conversion Platform for Experts: Despite its challenges (or perhaps because of them), this has become a legendary kit in the R/C conversion community. For experienced builders, it’s a known quantity with documented solutions.

Challenging and Engaging Build Process: The unusual half-shell construction and overall complexity create a genuinely engaging project that rewards patience and skill. Builders consistently report the satisfaction of solving its challenges.

Cons

Heavy Kit Wood Undermines Flight Performance: The dense balsa, while well-cut, is consistently too heavy for serious free-flight work. This isn’t a trim issue; it’s a fundamental material problem.

Severe Tail-Heavy Design Makes Free Flight Difficult: The accurate “short nose” scale reproduction creates a center of gravity nightmare. Rubber-powered flight requires excessive nose weight, creating a performance-killing cycle.

Basic Plastic Detail Parts Need Replacement: The included scale components lack detail and finish quality. Achieving impressive results requires aftermarket parts or scratch-building.

Expert-Only R/C Conversion Complexity: Successfully converting this kit requires re-engineering wing incidence, solving severe balance problems, aggressive weight reduction, and possibly redesigning control surfaces. It’s not a project for intermediate builders.

Why You’ll Simply Love this Plane

Despite everything I’ve just told you about the challenges, there’s a reason experienced builders keep returning to this kit. Let me explain the appeal.

There’s genuine joy in working with those laser-cut parts. When you’re building the complex half-shell fuselage and every former slots perfectly into place, when ribs align exactly as they should, you experience the satisfaction of a precision puzzle coming together. One builder put it simply: the build “went together so nice it was hard to put down.” That’s the feeling you’re chasing.

For the right builder, solving this kit’s famous challenges creates a powerful sense of accomplishment. When you’ve successfully balanced an R/C conversion, when you’ve engineered solutions to the tail-heavy problem, when you’ve built in the lightness needed to make this heavy airframe fly—you’ve genuinely earned something. The difficulty is the point. This isn’t a kit that holds your hand; it’s one that tests your skills and rewards your persistence.

The historical connection matters more than you might expect. You’re not just building a model; you’re reconstructing a piece of World War I aviation history. The Nieuport 11 fought in the skies over France, flown by the legendary Lafayette Escadrille. When your build is complete, whether it flies or hangs from your ceiling, it’s a tangible connection to those “magnificent war birds of the 1914-1918 era.” For aviation enthusiasts, that historical weight adds meaning to every hour spent at the building board.

And honestly? Even if it never leaves the ground, a well-built Nieuport 11 is simply beautiful. That distinctive biplane silhouette, the rotary engine cowl, the WWI color scheme—it’s a “great looking plane” that commands attention. Builders consistently describe their finished models as handsome birds that look fantastic displayed in a workshop or hanging from a ceiling. The aesthetic appeal alone justifies the build for many modelers.

Who Should Buy It

The Expert R/C Conversion Specialist

You’re the primary market for this kit, even if Guillow’s doesn’t realize it. You have experience with micro electric power systems, you understand aerodynamic principles like decalage and center of gravity management, and you’re genuinely energized by problem-solving. You see the “heavy” wood and “tail-heavy” design not as fatal flaws but as the starting challenge in an expert-level project.

You’re proficient at “building in lightness”—you know how to scallop a fuselage, select ultra-light covering, and carefully balance component placement. You have the skills to re-engineer wing incidence, possibly redesign control surfaces, and achieve the aggressive 7-ounce target weight this kit demands for successful R/C flight. For you, this kit’s reputation in the conversion community is a feature, not a warning.

The Patient Scale Display Builder

Flying isn’t your goal. You’re a World War I aviation enthusiast who loves the meditative process of stick-and-tissue construction. Your objective is a museum-quality display piece, and you’ll take genuine pleasure in working with those precision laser-cut parts. You’re not worried about the heavy wood because you’re not concerned with flight performance.

You’ll likely supplement or replace the basic plastic components, perhaps scratch-building interior details, gun sights, and control linkages to bring the model up to the level of detail you envision. You have the patience for tissue work, the steady hand for applying dope, and the willingness to spend weeks or months on a single build. The Nieuport 11’s scale accuracy and historical significance make it exactly the project you’re looking for.

The Nostalgic Guillow’s Traditionalist

You grew up building Guillow’s kits and you’re drawn to this one for the brand legacy and the building process itself. You understand that this is a serious project, not a weekend flier. You appreciate the engineering challenge of the half-shell construction and you’re not expecting contest-winning performance. You might attempt a rubber-powered build fully aware of the balance challenges, accepting that success will require patience, clay, and possibly multiple attempts. The journey is the reward.

Who Should Absolutely Avoid This Kit

First-Time Builders: That “Ages 14+” on the box is dangerously misleading. The complex construction, tissue covering, and inherent balance problems require experience that first-time builders simply don’t have. You’ll be frustrated and disappointed. Start with a simpler Guillow’s kit or a different manufacturer’s beginner-friendly design.

Competitive Free-Flight Modelers: If you’re flying for performance, distance, or competition, walk away. This kit is fundamentally “way too heavy” and the “short nose” creates balance problems that can’t be solved without compromising flight even further. Competition fliers should choose a performance-oriented manufacturer with a proven track record in serious free-flight design.

Casual Hobbyists Seeking Quick Success: If you want something that’ll look good and fly well within a weekend or two of work, this isn’t it. The Nieuport 11 demands significant time investment, problem-solving, and likely multiple building sessions. There are easier paths to flying satisfaction.

Important Considerations Before You Buy

This Is Not a Beginner-Friendly Free-Flight Kit

Despite being sold as a rubber-powered free-flight model, its performance in that role is genuinely poor. The heavy construction and severe balance problems make it “hard to get flying.” If you purchase this kit expecting an enjoyable rubber-powered flying experience, you’ll be disappointed. That’s not a warning about your skills; it’s a warning about the kit’s design limitations.

The Short Nose Problem Is Structural, Not Fixable

The tail-heavy condition isn’t something you can trim out with adjustments. The short nose of the WWI rotary engine design creates a center of gravity that’s fundamentally wrong for both free flight and R/C. For free flight, you’ll need substantial clay or lead weight in the nose, which kills flight performance. For R/C, you must place every single electronic component forward of the bottom wing’s leading edge, often requiring vertical battery mounting directly behind the firewall. Plan your build around this constraint from day one.

The Kit Wood Is Heavy—Plan Accordingly

Don’t expect lightweight, contest-grade balsa. Even with the precision laser cutting, builders consistently report the wood is denser than ideal. R/C converters must plan aggressive weight reduction strategies: scalloping the fuselage, replacing tail wood with lighter stock, using the lightest possible covering material, and carefully weighing every component before installation. Some builders recommend replacing the heavier tail pieces entirely with lighter wood purchased separately.

R/C Conversion Requires Re-Engineering, Not Just Following Plans

You cannot simply install servos and follow the kit instructions. The free-flight plan specifications are wrong for R/C flight. Successful builders recommend setting the top wing to +2 degrees positive incidence and the bottom wing to 0 degrees (neutral incidence), not the angles shown in the plans. The center of gravity must be set at approximately 10mm aft of the bottom wing’s leading edge—a narrow target with little margin for error. For three-channel setups without ailerons, the slow turn rate may require engineering a full-flying rudder. Budget time for test flights, adjustments, and likely multiple iterations to achieve stable flight.

The Plastic Detail Parts Are Placeholders

If you’re building for display and you care about scale accuracy, plan to purchase aftermarket detail parts or scratch-build replacements. The included plastic radial engine, machine gun, pilot figure, and cowl are functional but lack the detail serious scale builders expect. Williams Brothers cylinder kits are popular upgrades, or you can fabricate your own valve stems, control linkages, and interior details from balsa and wire.

Scale Confirmation: It’s 1/12, Not 1/14

You’ll see conflicting information online. The official Guillow’s manufacturer website lists this as 1/12 scale. Many retailers incorrectly list it as 1/14. The manufacturer’s specification is the authoritative source. If you’re planning to add aftermarket details or compare to historical references, use 1/12 as your scale factor.

Setup and Getting Started

For All Builds

Before you glue a single piece, study build logs from experienced modelers who’ve documented their processes online. Understanding the “unusual” half-shell fuselage construction before you start will save you from mistakes. Weigh your balsa components and identify the heaviest pieces. Use the lightest wood in the tail section—every extra gram behind the wings makes the balance problem worse.

Guillow’s recommends reinforcing the landing gear with wire, and experienced builders agree it’s essential. Use wire reinforcement on the struts; the added weight in the front is actually beneficial for the balance problem, and the strength prevents landing gear failures.

For Rubber-Powered Free-Flight Attempts

Make the nose block or cowl removable. This is the only practical way to add the substantial nose weight required for balance and to load the rubber motor. If you permanently glue the nose in place, you’ll regret it when you’re trying to add clay and access the motor. Some builders create a magnetic or friction-fit nose attachment system that allows easy removal.

For R/C Conversions

Design your component tray and mounting system before cutting wood. All electronics must go forward—plan for vertical battery mounting directly behind the firewall, with the receiver and servos immediately behind that. Some builders create a removable tray system that allows access to electronics without disassembling the fuselage.

Target a center of gravity of 10mm aft of the bottom wing’s leading edge. Mark this position clearly on your fuselage and check it repeatedly during the build. Adjust component placement as needed, knowing that 5mm too far aft can make the plane nearly uncontrollable.

Set your wing incidence properly from the start: +2 degrees on the top wing, 0 degrees (neutral) on the bottom wing. Ignore the free-flight specifications in the plans. These angles are critical for stable R/C flight and changing them after assembly is nearly impossible.

If building a three-channel system without ailerons, seriously consider engineering a full-flying rudder to improve turn performance. The low wing area creates a slow-responding aircraft; enhanced rudder authority helps compensate.

Target an all-up weight of 7 ounces or less. This requires discipline. Scallop the fuselage where possible, use the lightest covering material you can find, carefully select the lightest compatible motor and battery, and weigh every component before installation. The 147 square inch wing area demands extremely low wing loading for predictable flight characteristics.

Pricing and Value Assessment

Guillow’s lists the manufacturer’s suggested retail price at $106.99, but you’ll rarely pay that. Online hobby retailers typically sell this kit for $80 to $85, with occasional sales dropping it to around $68. That $80 to $100 street price is what you should expect to pay.

Here’s the value proposition reality: you’re not paying for premium materials. The balsa is heavy, the plastic parts are basic, and the tissue covering is standard grade. What you’re buying is intellectual property—the engineering of those precision laser-cut parts, the cleverness of the structural design, the Guillow’s brand legacy, and access to a well-documented platform with an extensive community of builders who’ve solved its problems.

For expert R/C converters and serious scale display builders, that $80 to $100 investment is justified. You’re getting a legitimate challenge with known solutions, a historically significant subject, and the satisfaction of completing a difficult project. The cost per hour of engaged building time is actually quite reasonable.

For anyone else—beginners, casual fliers, competitive free-flight modelers—this kit represents poor value. You’ll spend the same money on a project that’s likely to frustrate you and potentially never fly successfully. In that scenario, the materials cost is irrelevant because you’re paying for an unsatisfying experience.

Final Verdict

The Guillow’s Nieuport 11 “Bébé” is a kit at war with itself. It’s a modern product with genuinely impressive laser-cut precision, trapped in a vintage design philosophy that prioritizes scale accuracy over practical performance. That tension defines everything about the building and flying experience.

I cannot recommend this kit for beginners, despite what the “Ages 14+” label suggests. I cannot recommend it for hobbyists seeking a functional rubber-powered free-flight model—the inherent short nose design and heavy materials make that application genuinely frustrating.

But I can enthusiastically recommend it for two specific audiences: expert R/C conversion specialists who thrive on complex challenges, and patient scale display builders who prioritize historical accuracy and stick-and-tissue craftsmanship over flight performance.

For those right audiences, this is genuinely excellent. The laser-cut parts deliver the precision that makes a complex build manageable. The historical subject matter is compelling. The challenge is real but solvable. And the sense of accomplishment when you successfully balance and fly an R/C conversion, or complete a museum-quality display piece, is substantial.

The key to satisfaction with this kit is honest self-assessment before you buy. If you’re an expert who sees the “heavy” wood and “short nose” as the starting point for an engaging project, if you’re energized rather than discouraged by the R/C conversion challenges, if you’re a patient craftsman who values the building process and historical connection above flight performance—then you already know this kit is right for you.

If you’re still learning the fundamentals, if you want something that flies well on rubber power, if you’re looking for quick weekend satisfaction—choose a different kit. The Nieuport 11 will respect your skills and reward your patience, but only if you come to it with the right expectations and experience level.

Know yourself. Know this kit’s challenges. And make the decision that serves your actual goals, not the marketing on the box.

Key Takeaways

- Modern precision meets vintage flaws: Excellent laser-cut parts deliver impressive fit, but heavy balsa and inherent “short nose” balance problems undermine free-flight performance—this is an expert’s challenge, not a beginner’s kit despite the “Ages 14+” label.

- R/C conversion is the real purpose: The kit has become legendary in the conversion community, but success demands aggressive weight reduction, re-engineered wing incidence, forward component placement, and solving severe tail-heavy balance issues—target 7 oz. all-up weight with CG 10mm aft of bottom wing leading edge.

- Perfect for the right builder only: Expert R/C specialists seeking a documented challenge and patient scale display builders prioritizing historical accuracy will find genuine satisfaction; competitive free-flight modelers and beginners should choose different kits.

- Budget for aftermarket upgrades: The included plastic detail parts are functional placeholders requiring replacement or enhancement for museum-quality results—successful builders immediately turn to Williams Brothers components or scratch-built details.

- Historical significance adds value: As a scale reproduction of the Lafayette Escadrille’s legendary WWI fighter, this kit rewards builders with a tangible connection to aviation history and a striking display piece, even if flight performance disappoints.