Stop blaming your building skills. The reason your scale aircraft looks like a plastic toy isn’t a construction error—it’s a finish problem rooted in physics, and you can correct it with three specific techniques in less time than it takes to watch a sitcom.

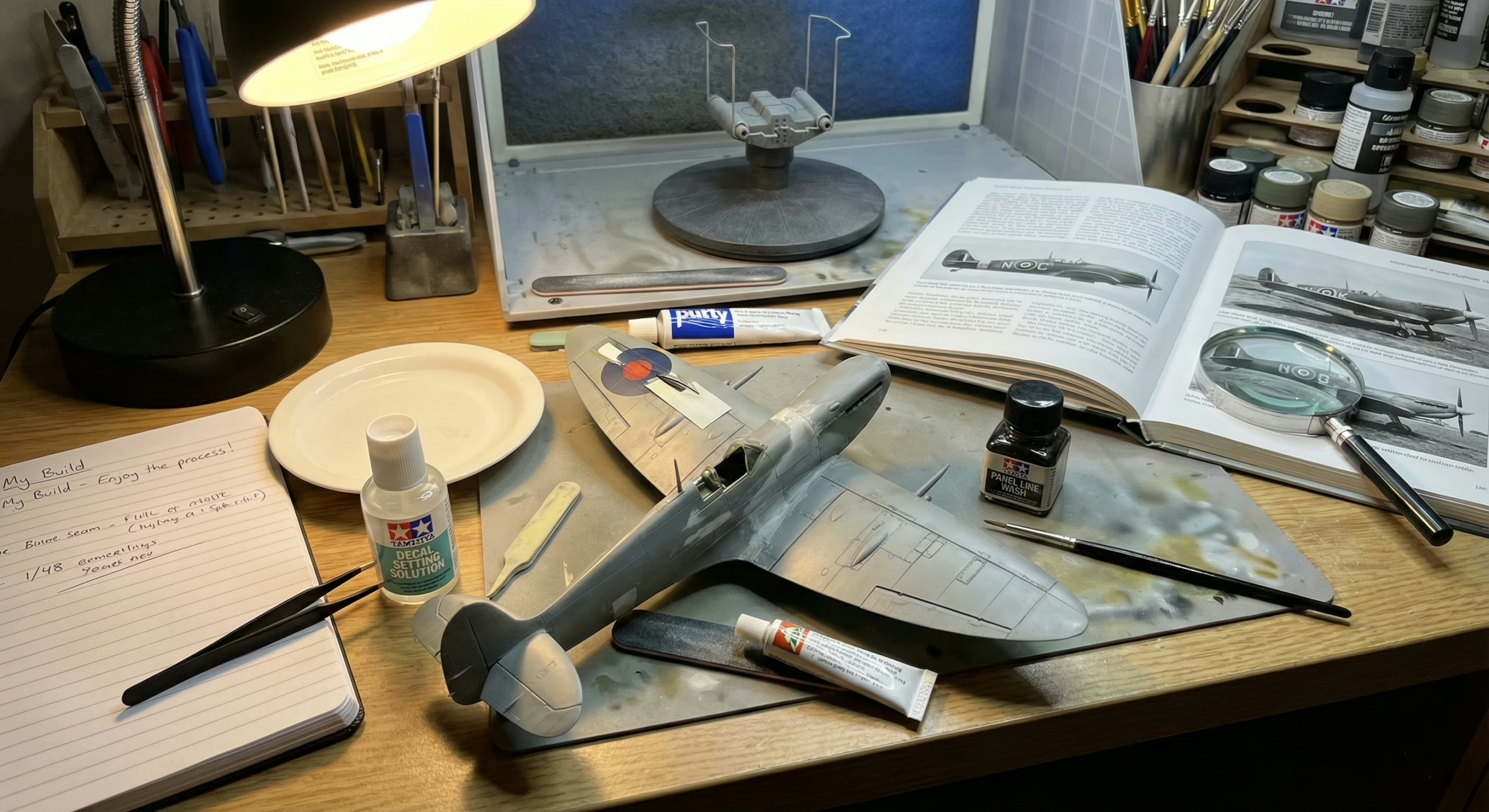

You’ve spent hours carefully assembling your latest kit. You’ve sanded every seam until it disappeared, applied paint with surgical precision, and placed decals exactly where they belong. You step back to admire your work—and something’s wrong. Despite all your effort, the model still looks like a die-cast toy rather than a realistic representation of a combat aircraft.

This frustrating phenomenon isn’t a failure of your building technique. It’s a failure of surface finish management. The “toy-like” appearance stems from three specific visual cues that betray the model’s material origins: incorrect light reflection (wrong sheen), visible carrier film (decal silvering), and unnatural color uniformity (monochrome finish). When viewers perceive a scale model as “plastic,” their brains are processing optical data about how light interacts with the surface.

Here’s the good news: the transition from “toy” to “replica” doesn’t require years of artistic training. You can achieve it through a rapid, three-step correction protocol involving sheen adjustment, decal integration, and tonal variation. The final 5% of the build process contributes to 80% of the visual realism. By addressing the physics of how light interacts with your model’s surface, you can effectively trick the observer’s eye into perceiving weight, mass, and material authenticity.

The psychological impact of a toy-like finish can’t be overstated. It leads to discouragement, abandoned projects, and the mistaken belief that more expensive kits will solve a finishing problem. But the root cause is rarely the kit itself. A $200 resin masterpiece finished with high-gloss sheen will look less realistic than a $20 snap-together kit finished with proper matte coating and tonal variation. Understanding this distinction lets you focus your efforts where they yield the highest return: the final finish.

The Real Culprit: Understanding Paint Sheen

The Real Culprit: Understanding Paint Sheen

Why Sheen Matters

The primary difference between a realistic scale replica and a toy is how light reflects off its surface. To understand why models look plastic, you need to grasp the difference between specular and diffuse reflection.

When light hits a smooth surface like glossy plastic or high-gloss paint, it reflects at a single angle—the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence. This creates a concentrated, mirror-like highlight known as “glare.” Our brains associate high specular reflection with smooth, manufactured materials like plastic, glass, or polished metal. A model painted with glossy paint retains the high specular reflection characteristic of bare plastic, reinforcing the perception of the object as a small, synthetic item. The smoothness allows light rays to bounce off in a unified direction, creating a sharp image of the light source on the model’s surface.

When light hits a rough surface, it scatters in many different directions. This scattering diffuses the light, eliminating hard glare and softening the surface appearance. Military aircraft, particularly combat theater aircraft, typically feature matte or low-sheen finishes designed to minimize visibility. The microscopic roughness of flat paint breaks up light waves, simulating the non-reflective nature of heavy industrial coatings, oxidized aluminum, or fabric dope. This diffusion is crucial for realism. It softens the visual edges of the object, blending it into its environment and giving it a sense of mass and solidity.

Applying a gloss finish to a subject that should be matte creates cognitive dissonance. The viewer knows the object represents a 30-ton warplane, but the optical feedback suggests a 4-ounce plastic object. The “toy-like” look results from specular overload—too much coherent light bouncing back to the viewer’s eye. This overload prevents the eye from perceiving the subtle details of form and texture that give a model its sense of scale.

Even when a full-scale aircraft is glossy—such as a modern airshow performer or pristine VIP transport—applying a full gloss finish to a scale model often looks incorrect. This is due to the Scale Gloss Effect. In the real world, atmospheric particulates like dust, moisture, and pollen scatter light between the observer and the object, naturally muting the intensity of highlights over distance.

When you view a 1/48 scale model from one foot away, you’re simulating a view of the real aircraft from 48 feet away. At that scale distance, the high-intensity specular highlights seen on a real car bumper or wet aircraft skin are diffused by the atmosphere. A model with a “wet” high-gloss finish ignores this atmospheric diffusion, appearing hyper-real and, consequently, toy-like. Experts suggest that “scale gloss” should actually be represented as a satin or semi-gloss finish to mimic how light behaves over distance.

The Visual Impact of Wrong Sheen

The visual impact of incorrect sheen is immediate, emphasizing the “plasticity” of the underlying material.

A glossy fuselage reflects room lighting—lamps, windows—clearly. These reflections are distinct “tells” of a small object. On a real aircraft, reflections are broken up by surface irregularities, rivets, and the matte nature of the paint. The fuselage curvature acts as a convex mirror, distorting and magnifying these reflections. On a model, this effect is exaggerated, drawing attention to the surface’s artificiality. A matte finish eliminates these distractions, allowing viewers to appreciate the form and detail without interference.

Fabric-covered control surfaces on WWII aircraft were doped and matte. If these reflect light identically to metal cowlings, the illusion of mixed materials is lost. The texture of fabric is fundamentally different from metal, and this difference should be reflected in the finish. By masking off fabric areas and treating them with a flatter clear coat than metal sections, you can create subtle but effective contrast that enhances realism.

Die-cast metal toys are heavily clear-coated to protect paint. A modeler who leaves high sheen on a military subject inadvertently replicates the finish of a Hot Wheels car rather than a combat vehicle. This association with toys is hard to shake. The high-gloss finish is a hallmark of mass-produced, durable playthings.

Consequently, the single most effective step to removing the toy-like appearance is to virtually eliminate specular reflection through application of a flat (matte) clear coat. This forces light to scatter, simulating the texture of heavy military paint and oxidized metal, which the brain interprets as “heavy” and “real.”

The Decal Silvering Effect: When Clear Film Betrays You

The Decal Silvering Effect: When Clear Film Betrays You

What Is Silvering and Why It Happens

The second major contributor to a toy-like appearance is decal silvering. This phenomenon manifests as a milky, shimmering, or silver halo surrounding printed markings on a model. It instantly breaks immersion, revealing that markings are stickers sitting on top of the surface rather than paint integrated into the surface.

Silvering is caused by entrapment of microscopic air pockets between the clear carrier film of the decal and the model’s surface. Flat (matte) paints achieve their non-reflective finish through rough surface texture at the microscopic level. This texture resembles a mountain range of pigment particles. This roughness diffuses light but creates a hostile environment for decal adhesion.

When a decal is applied over this rough terrain, the carrier film sits on the “peaks” of paint particles, bridging over the “valleys.” The film is too rigid to conform to the microscopic irregularities without assistance. The valleys remain filled with air. When light passes through the clear carrier film and hits these air pockets, it refracts and scatters differently than it does where the film adheres to paint. This scattered light creates the visible “silver” interference pattern. The air gap acts as a mirror, reflecting light back to the viewer and highlighting non-adhered areas.

The Visibility Problem

Silvering is particularly insidious because it often becomes visible only after the model has dried or when viewed from oblique angles. Under direct lighting, the decal may appear adhered, but shifting the viewing angle reveals the reflective air gap. This shift in visibility is jarring and breaks the illusion of a painted marking.

Real aircraft markings are painted on using stencils. They have no “edge” or “film.” Silvering highlights decal edges, emphasizing that it’s a separate, added element—a sticker. This destroys integration of the marking with the airframe, making it look like a superficial addition rather than an integral part of the aircraft’s identity.

On dark camouflage schemes, silvering stands out as a bright, jagged outline, destroying the model’s tonal balance. Dark greens, grays, and blacks are particularly unforgiving of silvering, as the contrast between paint and silvered film is maximized. Silvering creates a physical barrier that prevents weathering washes from flowing over markings naturally. A wash will often wick around the silvered edge, creating a dark, dirty ring that further highlights the defect. Instead of grime settling into panel lines and recesses, it accumulates around the decal, drawing attention to the flaw.

The presence of silvering is a definitive marker of an amateur finish. It signals a failure to prepare the surface or treat the decal, reinforcing the “toy” aesthetic where markings are essentially stickers applied to plastic.

The Missing Depth: Why Your Model Lacks Dimension

The Missing Depth: Why Your Model Lacks Dimension

The Monochrome Problem

A plastic kit molded in gray and painted with a single, uniform coat of “Gunship Gray” looks indistinguishable from a toy molded in colored plastic. This is the Monochrome Problem.

In the natural world, and particularly in operational machinery, colors are rarely uniform. Sunlight, rain, hydraulic leaks, maintenance touch-ups, and heat cycles alter the chemical composition of paint, causing it to fade, chalk, or darken in random patterns. A uniform coat of paint implies that the object just rolled off the assembly line and has never seen daylight. Even then, manufacturing variations would likely introduce some subtle tonal shifts.

As discussed regarding sheen, looking at a model is akin to looking at a real object from a distance. Atmosphere not only diffuses light (gloss) but also desaturates color. A solid block of undiluted color on a model appears too dark and too intense because it lacks the “aerial perspective” that softens colors over distance. This atmospheric perspective causes distant objects to appear lighter and bluer than they are close up.

Without tonal variation, the human eye perceives the model as a single mass of plastic. It lacks the visual cues of structure—ribs, spars, panels—that deeper tonal variation provides. The model looks flat and two-dimensional, despite being a 3D object. Tonal variation helps to define the shape and volume of the aircraft, highlighting curves and recesses that might otherwise be lost in a uniform field of color.

The Factory-Fresh Trap

Beginners often fall into the trap of desiring a “perfect” finish—uniform paint, crisp lines, and zero weathering. However, in scale modeling, “perfect” equals “plastic.” Even an aircraft fresh from the factory line possesses subtle variations.

Different panels may be made of different alloys or composites, holding paint differently. Metal panels may reflect light differently than composite radomes or fabric control surfaces, creating subtle shifts in color and sheen. Rivet lines and panel joins create minute shadows and highlights that break up the surface. The process of riveting skin panels creates slight deformations in the metal, which catch light in varying ways. This “oil canning” effect is a hallmark of stressed-skin aircraft construction and should be represented, however subtly, on the model.

When a model is painted perfectly uniformly, the addition of brightly colored decals can visually “crush” the underlying paint work, making it look simpler than it is. Tonal variation is required to balance the high contrast of the markings. The bright reds, blues, and yellows of national insignia can overpower subtle camouflage colors, making the model look toy-like. By fading the paint and decals together, you integrate the markings into the overall finish.

To escape the toy-like appearance, you must introduce entropy—the visual evidence of disorder and wear. This doesn’t necessarily mean heavy mud and rust (which can be inappropriate for aircraft), but rather the subtle shifting of hues that suggests the object exists in a real environment.

The Three-Step Fix: Transform Your Model in Under 30 Minutes

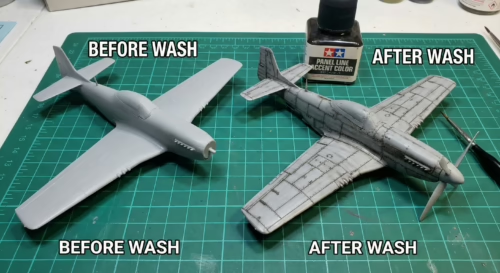

The following protocol outlines a rapid, high-impact workflow to correct sheen, silvering, and tonal monotony. While the chemical curing times for these steps extend beyond 30 minutes, the active application time for the fixes is roughly half an hour.

Step 1: Apply the Correct Final Finish (10 Minutes)

The most dramatic transformation comes from unifying surface sheen with a clear flat coat. This eliminates the “plastic glare” and simulates the diffuse reflection of real military paint.

Flat varnishes work by suspending microscopic matting agents (often silica or talc) in a clear carrier. As the solvent evaporates, these particles remain on the surface, creating a microscopically rough texture that scatters light. The concentration and size of these particles determine the degree of flatness. A “dead flat” finish has a high concentration of coarse particles, while a satin finish has fewer, finer particles.

Application Protocol:

First, ensure the model is completely dry and free of dust. Use a tack cloth or anti-static brush to remove any lint or particles that might be trapped in the clear coat.

For product selection, Testors Dullcote (lacquer-based) is the industry standard for a “dead flat” finish that is durable and non-yellowing. Alclad II Klear Kote Flat (ALC-314) is another excellent lacquer option that dries quickly. For acrylic users, Tamiya Flat Base (X-21) mixed with a gloss carrier (like Future/Pledge) is effective, but X-21 cannot be sprayed alone as it will turn white.

For technique, apply the flat coat in light, misting passes from 6-8 inches away. Do not flood the surface. This prevents the solvent from attacking the underlying paint or decals. Ensure 100% coverage—any glossy spots remaining will ruin the illusion. Check the model under strong light to identify any missed areas.

As the solvent flashes off (usually within seconds for lacquers), the model will visibly transform. The “toy” shine disappears, and colors will appear slightly lighter and more integrated. This “flat coat shift” is a normal optical phenomenon and should be anticipated when mixing base colors.

Time Investment: 10 minutes active spraying.

Step 2: Prevent or Fix Decal Silvering (10-15 Minutes)

To integrate decals so they look painted on, the air gaps causing silvering must be eliminated. This is done through surface preparation and chemical softening.

Prevention Protocol (The Gloss Base):

Before applying decals, the model must be coated with a gloss finish. A gloss surface is microscopically smooth, allowing the decal film to lay flat with no air gaps. Apply a coat of Alclad Aqua Gloss, Tamiya Gloss (X-22), or Pledge Floor Gloss (Future) to the areas receiving decals. This creates the necessary smooth substrate. Ensure the gloss coat is fully cured before applying decals to prevent reactions with setting solutions.

Fixing Protocol (Setting Solutions):

If silvering occurs, or to ensure perfect conformity over rivets and panel lines, use a two-step chemical process.

Micro Set (Blue Bottle) is a mild acetic acid solution that wets the surface and prepares the decal. Apply under the decal to improve adhesion and reduce surface tension.

Micro Sol (Red Bottle) is a stronger solvent that softens the decal film, melting it into the paint texture. Apply over the decal once positioned. Do not touch the decal while it is soft—it will wrinkle (which is good) and then snuggle down flat as it dries. The wrinkling indicates that the solvent is working, breaking down the carrier film’s rigidity.

For stubborn silvering or thick decals (like Tamiya’s), use Walthers Solvaset. It is significantly stronger than Micro Sol. If a decal has already dried with silvering, prick the silvered area with a needle or hobby knife tip and flood it with Solvaset to force the fluid under the film. This allows the solvent to attack the silvering from the inside out.

Time Investment: 10-15 minutes active application.

Step 3: Add Subtle Tonal Variation (5-10 Minutes)

The final step breaks the monochrome monotony by simulating the effects of sunlight and oxidation. This technique is often called Post-Shading or Post-Fading.

Real aircraft paint fades from UV exposure, turning lighter and chalkier on upper surfaces. Prepare a highly thinned mixture of Flat White or Light Gray (e.g., Tamiya XF-2). The ratio should be extreme: 90% thinner to 10% paint, or even 95% thinner. The mixture should be translucent, barely tinting the surface. Using a highly thinned mix allows for gradual buildup of the effect, preventing mistakes.

Using an airbrush at low pressure (10-15 PSI), gently mist this mixture over the centers of panels on the upper fuselage and wings. Avoid the panel lines (which should remain darker). This creates a “cloudy” pattern that breaks up the solid color.

Do not be perfectly uniform. Vary the intensity to simulate uneven wear. Focus on areas that would receive the most direct sunlight—spine, upper wings. Consider the airflow over the wings and fuselage, streaking the fading back from the leading edges.

The centers of panels become slightly lighter/faded, while the edges and panel lines remain the original base color. This creates an instant 3D effect, adding “volume” to flat surfaces without the harshness of a black panel line wash. It mimics the way sunlight bleaches paint, giving the model a weathered, operational look.

Time Investment: 5-10 minutes active spraying.

The Results: What to Expect

The cumulative effect of these three steps is a radical shift in visual perception.

The Clear Flat Coat removes the specular highlights that scream “plastic,” replacing them with the diffuse, soft reflection of military-grade radar-absorbent paint or oxidized aluminum. The model now absorbs light like a heavy object, rather than reflecting it like a toy.

The Decal Treatment removes the visible edges of markings. Instead of stickers floating on top of the model, the markings appear to be painted onto the metal skin, weathering and fading along with the airframe. This seamless integration is key to the illusion of reality.

The Tonal Variation tricks the eye into seeing a heavy, large object subjected to the elements. The slight unevenness of the finish mimics the entropy of the real world, breaking the “toy” illusion of perfection. The model gains a sense of history and usage, telling a story beyond its mere form.

A viewer looking at a model treated with these steps will no longer focus on the model itself—the plastic, the glue seams—but on the subject it represents: the aircraft, the history. The “toy-like” quality evaporates, replaced by the weight and presence of a replica. This transformation is not subtle; it is a fundamental change in the character of the object.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even with these techniques, pitfalls exist that can ruin the finish.

Frosting (The White Haze)

The clear flat coat dries with a cloudy, white, “frosted” appearance, ruining the paint job. This occurs when spraying lacquer or enamel flat coats in high humidity causes moisture to become trapped in the drying paint. The rapid evaporation of the solvent cools the surface, causing condensation to form and become trapped in the finish. Not shaking the can or bottle enough allows the flattening agent (talc/silica) to clump, spraying white powder onto the model. Spraying too far causes the paint to dry in mid-air before hitting the model, landing as dusty particles.

To fix frosting, applying a thin layer of olive oil can sometimes clarify the varnish. The oil fills the microscopic pores of the frosted finish, restoring transparency. However, this is a temporary fix and can be messy. Spraying a wet coat of gloss varnish over the frosting can re-dissolve the matting agent and clarify the finish. The solvent in the gloss coat melts the frosted layer, allowing it to level out and become clear again. Once dry, a new flat coat can be applied.

To prevent frosting, always shake flat coats for 2+ minutes. Do not spray in humidity above 60%. Use a hair dryer to gently warm the surface before spraying to prevent condensation.

Silvering Persistence

Silvering remains even after using setting solutions. The underlying surface was too rough (matte paint) and the decal couldn’t conform. The air pockets are too large or numerous for the solvent to overcome.

To fix this, prick the silvered decal with a needle and apply Solvaset or a strong solvent. If that fails, carefully slice the decal along panel lines to release tension. In extreme cases, weather over the silvering with mud or chipping to hide it. Alternatively, carefully paint over the silvered area with the base color, effectively painting out the flaw.

Tonal Crush

The weathering and shading disappear after the final clear coat. Clear coats (especially gloss) can darken paint and reduce the contrast of subtle fading effects. The optical properties of the clear coat alter the way light reflects off the underlying pigment, muting the tonal variations.

To fix this, over-emphasize the tonal variation slightly during the painting stage. It will “calm down” under the final flat coat. Anticipate the darkening effect and paint your highlights a shade lighter than you think necessary.

Beyond the Basics: Next Steps in Weathering

The three-step fix described above solves the fundamental “toy-like” problem, but it is merely the foundation for advanced realism. Once you’ve mastered sheen, decals, and basic fading, you can explore panel line washes, oil dot filters, chipping, and exhaust and fluid staining.

Panel line washes use oil or enamel washes to darken recessed panel lines, simulating accumulated grime and shadow. This technique emphasizes the structural details of the aircraft and adds depth to the surface.

Oil dot filters involve applying dots of various oil paint colors—white, blue, yellow, ochre—and blending them into the surface to create complex, chromatic tonal variation. This mimics the subtle shifts in color caused by environmental exposure and chemical weathering.

Chipping simulates paint flaking off to reveal primer or bare metal in high-wear areas like wing roots and cockpits. This adds a layer of history to the model, suggesting use and maintenance.

Exhaust and fluid staining uses airbrushing or pigments to recreate the specific stains left by engine exhaust, hydraulic leaks, and gun residue. These stains are signature elements of operational aircraft and add a visceral sense of realism.

These advanced techniques rely on proper execution of the basic three steps. A wash won’t flow on a rough surface, and chipping looks fake on a glossy toy. Master the flat coat, the decal, and the fade, and the rest will follow.

Key Takeaways

- Real military aircraft are matte, not glossy. Apply a clear flat coat like Testors Dullcote as your final step to eliminate plastic shine and simulate heavy industrial paint.

- Decal silvering makes markings look like stickers. Prevent it by applying a gloss coat before decaling. Fix it with setting solutions like Micro Sol or Solvaset that melt the decal into the surface.

- Single-color paint jobs look plastic. Use post-shading—misting highly thinned lighter paint on panel centers—to simulate sun fading and add three-dimensional volume.

- Spraying flat clear coats in high humidity causes frosting, a white haze that ruins the finish. Always shake cans vigorously and spray in dry conditions.

- Follow the correct order: Paint → Gloss Coat → Decals → Setting Solution → Weathering → Final Flat Coat. This sequence protects your work and ensures a realistic, integrated result.