Choose wrong, and you’ll waste money. Choose right, and you’ll be flying loops in weeks. Here’s how to pick the power system that matches your learning style—not just your budget.

You’re standing in the hobby shop or scrolling through online listings, staring at two very different paths into RC aviation. One promises plug-and-play simplicity. The other offers the sound and feel of real flying. Both will teach you to fly, but they’ll take you on completely different journeys to get there.

I’ve watched dozens of newcomers make this choice, and here’s what matters: the “best” power system isn’t about which technology is superior. It’s about which one fits your life, your personality, and how you actually learn. Choose electric, and you’ll spend more time flying and less time wrenching. Choose gas, and you’ll become as much a mechanic as a pilot. Both work, but picking the wrong one for your situation leads to frustration and a dusty airplane in the garage.

This guide cuts through the forum debates and sales pitches to focus on what really matters: how each system affects your learning curve. We’ll walk through the actual field experience, the honest costs, and the specific skills you’ll develop. By the end, you’ll know which system matches your reality.

Understanding the Two Systems: What You’re Actually Choosing

Before we compare experiences, let’s establish what these systems actually are. Electric planes are battery-powered aircraft using brushless motors controlled by Electronic Speed Controllers. Think of them like cordless power tools—you charge the battery at home, plug it in at the field, and you’re ready to fly. The motor delivers instant torque the moment you advance the throttle stick.

Gas planes run miniature gasoline engines, typically two-stroke designs burning a mixture of pump gas and two-stroke oil. They’re scaled-down versions of the engines you’d find in a chainsaw or weed trimmer. These engines need to be started manually (or with an electric starter), warmed up, and tuned to run properly. They idle, they make noise, and they smell like Saturday morning lawn care.

The fundamental difference you’ll notice immediately is the startup ritual. With electric, you connect the battery and you’re done—the system is live. With gas, you’re choking, priming, flipping the propeller, adjusting carburetor needles, and hoping it catches. Neither is difficult once you know the procedure, but they demand different types of attention.

Power delivery also differs dramatically. Electric motors produce maximum torque instantly from zero RPM. Tap the throttle and the response is immediate. Gas engines need to spool up through their power band—there’s a fraction-of-a-second delay between your stick input and the engine reaching peak power. This isn’t a flaw; it’s just how internal combustion works. But it fundamentally changes how you fly.

Maintenance follows similar patterns. Electric systems need battery care, connector soldering, and occasional motor cleaning. Gas engines require fuel mixing, carburetor tuning, spark plug checks, and regular vibration inspections. The electric pilot becomes an electronics technician. The gas pilot becomes a small-engine mechanic.

The First Flight Reality: What Actually Happens at the Field

Let’s walk through your typical first flying session with each system.

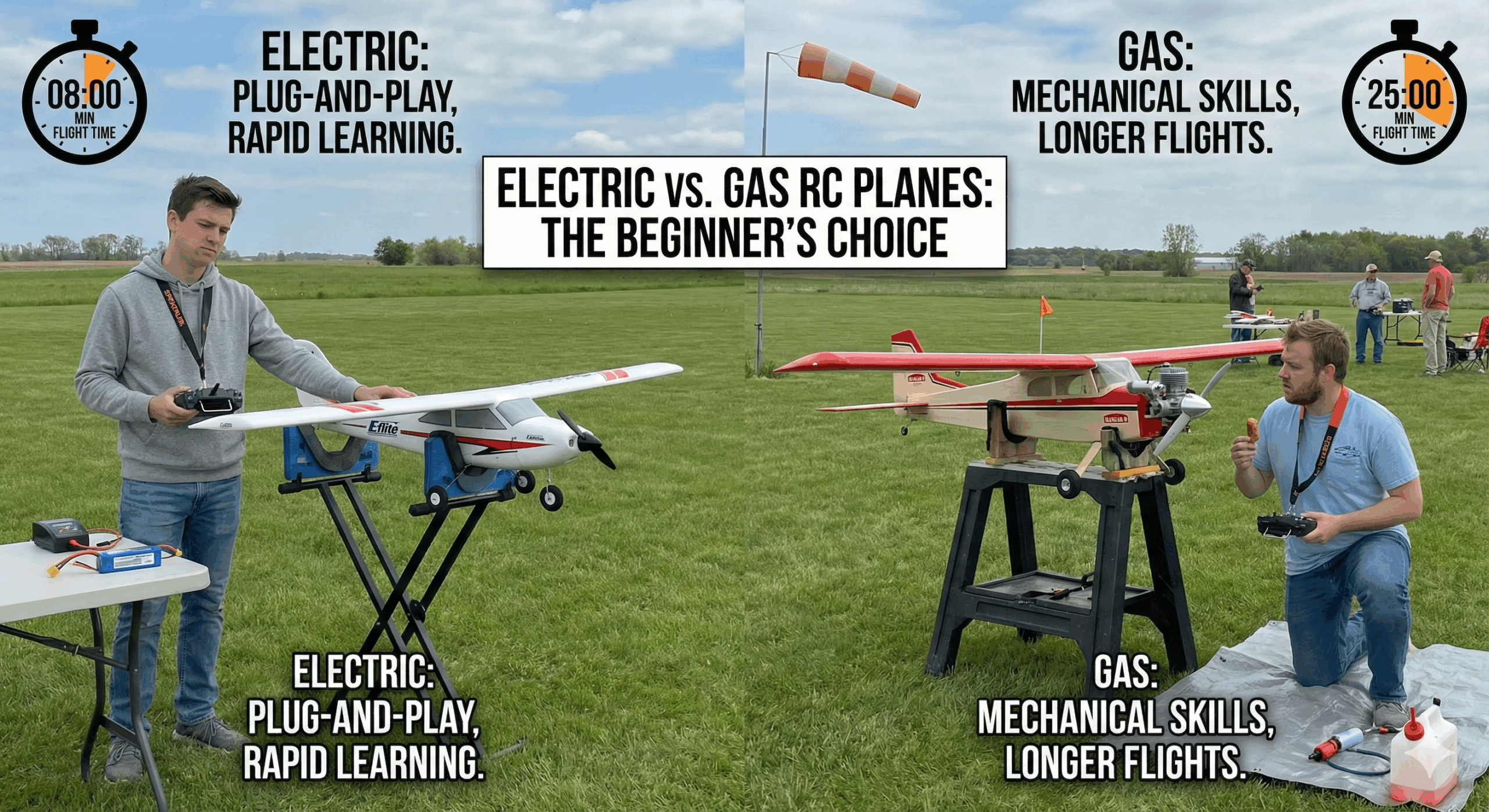

With an electric setup, your morning starts at home. You charged three battery packs overnight using your computerized charger. You packed them in a fireproof bag along with your plane, transmitter, and basic tools. At the field, you assemble the wing (usually two screws or rubber bands), plug in the battery, and perform a quick range check. Two minutes later, you’re ready to fly.

The anxiety with electric is duration. You’re constantly aware you have maybe eight minutes before the battery voltage drops too low. Many beginners land early out of fear, leaving power on the table. The flip side is turnover speed—if you brought three charged packs, you can fly three times in rapid succession. This repetition accelerates learning.

With a gas setup, your morning looks different. You arrive with a fuel jug, hand pump, electric starter, tools, and the airplane. First task: fueling. You pump gasoline mixed with two-stroke oil into the tank through Tygon tubing, being careful not to introduce air bubbles that can cause the engine to quit mid-flight.

Then comes the starting ritual. You close the choke and flip the propeller by hand (using a leather glove or “chicken stick” for safety) until you hear the engine pop once. That’s priming. You open the choke, set the throttle to just above idle, turn on the ignition system, and either flip again or use the electric starter. When it catches, the engine roars to life, settling into a lumpy idle.

But you’re not done. The engine needs to warm up to operating temperature. Then you advance the throttle to check the high-end needle setting. If it sputters or sounds rough, you shut down and adjust the carburetor with a screwdriver. This tuning process can take ten minutes on a cold engine. And here’s the reality many beginners don’t expect: you really should have a helper holding the tail while you start the engine. It’s a safety issue—gas planes lunge forward if they start at high throttle.

The stress with gas isn’t duration (you’ve got 20-30 minutes of flight time), it’s reliability. You’re praying the engine doesn’t quit on takeoff. That anxiety keeps your attention sharp but can be intimidating at first.

Both systems have their moments of frustration. Electric pilots experience “dead stick” landings when they misjudge battery capacity. Gas pilots deal with engines that won’t start because the carburetor needs adjustment. Neither is inherently harder—they’re just different problems requiring different solutions.

Learning to Fly: How Power Delivery Affects Your Progress

Here’s where the power system choice fundamentally alters your learning path. The way thrust is delivered shapes the reflexes you develop and the skills you prioritize.

Phase 1: First Circuits (Flights 1-5)

With electric power, you’ll immediately notice how precise your throttle control needs to be. That instant torque means small stick movements create immediate responses. Overcorrect and the plane leaps upward. Undercorrect and it sinks fast. You’re learning to make tiny, deliberate inputs rather than large sweeping movements.

The huge advantage here is recovery capability. If you stall the wing or get into a bad attitude, a burst of throttle instantly energizes the airframe and blasts air over the control surfaces. This “get out of jail free” card builds confidence rapidly. You learn that mistakes are recoverable, which encourages experimentation. Most electric beginners achieve their first solo circuits within two to three weekends.

Gas power demands a different approach. That throttle delay means you need to anticipate power needs rather than react to them. You’re learning to plan two seconds ahead—if you want power now, you should have started advancing the throttle two seconds ago. This enforces better discipline regarding airspeed and energy management. You can’t simply punch out of trouble, so you learn not to get into trouble in the first place.

The downside is slower initial progress. Many gas beginners spend their first two sessions just learning to start and tune the engine. Actual flight time is limited. Solo flight might not happen until month two. But by forcing you to think ahead, gas teaches better fundamental habits earlier.

Phase 2: Basic Maneuvers (Flights 6-20)

As you progress into turns, climbs, and pattern work, the systems continue to teach different lessons. Electric pilots develop excellent throttle modulation for precise approaches. Within ten flights, you’ll be making smooth power adjustments to nail your landing spot. The instant response lets you “feel” the connection between throttle and airspeed.

But there’s a trap here. Some electric pilots develop a bad habit: using power to compensate for poor planning. Approaching too fast? Kill the throttle. Too slow? Blast it. The airplane tolerates this sloppiness because it’s so responsive. You’re flying with the motor instead of flying the wing.

Gas pilots can’t cheat this way. The heavier airframe with higher wing loading carries momentum. The engine provides residual thrust even at idle. You learn to set up stabilized approaches—establishing your descent rate and airspeed far from the runway and holding them steady. This mirrors full-scale aviation technique. Your landings take longer to master, but when you get them right, they’re smooth.

The sound factor is also significant. With gas, you’re flying by ear as much as by eye. The Doppler shift tells you the plane’s speed. When the engine loads up and the RPM drops, you know the nose is high and the plane is climbing steeply. When it screams, you know you’re diving. This auditory feedback creates an extra information channel. Electric pilots must rely almost entirely on visual cues, which sharpens your visual pattern recognition but leaves you without that sonic telemetry.

Phase 3: Developing Feel (Flights 21-50)

By this point, the skill gap starts narrowing. Electric pilots are attempting loops and rolls, though they may struggle with landing precision in windy conditions because they haven’t developed deep energy management skills. Gas pilots are comfortable with engine operation and are logging serious flight time. Their landings are often more consistent because the heavier plane provides more stability.

Here’s something worth noting: gas pilots will eventually experience a dead-stick landing—the engine quits and they’re forced to glide in without power. This terrifying event actually teaches emergency procedures that electric pilots rarely encounter. You learn best glide speed, how to preserve altitude, and how to commit to a landing spot without a go-around option. It’s stressful, but it makes you a more complete pilot.

The Maintenance Learning Curve

Maintenance represents a secondary curriculum, and your power choice determines which technical skills you’ll develop.

Electric maintenance is relatively clean and electronic. Your primary task is battery management. LiPo batteries degrade if stored fully charged, so after each session you need to discharge packs to storage voltage using your charger. Fail to do this and the internal resistance increases, turning a good battery into garbage within a season. You’ll also monitor the milliohm resistance in each cell to predict failure before it happens.

You’ll learn soldering for high-current connectors. Cold solder joints cause crashes, so proper technique matters. You’ll understand Ohm’s Law—how voltage, current, and resistance interact. The motor might need bearing replacement after a hundred flights. But overall, electric maintenance leaves more time for actual flying.

Gas maintenance is extensive and dirty. After every flying session, you’re checking for loose screws—the combustion vibration tries to disassemble your airframe. Every metal-to-metal fastener needs blue Loctite to stay tight. You’ll inspect the firewall for cracks, check servo mounting screws, and ensure the engine mount bolts haven’t backed out.

The fuel system requires attention too. Gasoline hardens Tygon fuel lines over time, so you’re replacing them annually. The tiny mesh screen inside the carburetor clogs with microscopic debris and needs regular cleaning. If the engine sits unused for months, the metering diaphragms stiffen and you’re rebuilding the carburetor.

Winterization is mandatory. Ethanol in modern gasoline attracts moisture and corrodes aluminum parts. You can’t just shelve a gas engine for the season—you need to run it dry or treat it with after-run oil to protect the piston ring and bearings.

The trade-off is educational. Gas pilots develop mechanical sympathy—they understand how machines work and how materials fail. Electric pilots develop procedural discipline—they understand system management and electrical theory. Both are valuable skill sets, just aimed at different domains.

Cost Comparison: The Real Numbers Behind Getting Airborne

Let’s cut through the marketing and look at actual costs. The common wisdom is “electric is cheap, gas is expensive,” but the reality depends on how often you fly.

For electric, a complete starter package runs $400 to $600. That includes a quality Ready-to-Fly trainer like the E-flite Apprentice STS ($300), a computerized charger ($60), and three battery packs ($50 each). You’ll also need connectors, tools, and spare propellers ($30-50). This gets you genuinely flight-ready.

For gas, expect $800 to $1,200 initial investment. An Almost-Ready-to-Fly airframe like the Hangar 9 Alpha 40 costs around $250. A quality engine (DLE 20RA or similar) adds $300. You’ll need servos and electronics ($200), field support gear including an electric starter, fuel pump, and fuel container ($150), plus tools and initial fuel supply ($100). The upfront cost is definitely higher.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Over your first year, assuming you fly 50 times, the operating costs reveal a different picture. Electric seems free—you’re charging at home, and residential electricity costs pennies. But batteries are consumables. A $50 LiPo pack lasts 100 to 150 charge cycles before performance degrades unacceptably. Spread that cost across flights and you’re paying $0.30 to $0.50 per flight in battery amortization.

Gas costs about $0.30 per flight in actual fuel. A 20cc engine burns roughly 10 ounces per flight, and a gallon of mixed fuel yields 12 to 15 flights. Current gasoline prices make this remarkably economical.

The crash variable also matters. Electric foam planes repair easily with CA glue. Parts are cheap. Gas planes use balsa and plywood construction—they shatter on impact. A hard landing can bend a crankshaft or crack cooling fins, adding $50 to $100 to your repair bill beyond the airframe damage.

Resale values differ too. Quality gas engines from brands like Desert Aircraft, O.S., or DLE retain 60 to 70 percent of their purchase price. They’re liquid assets in the used market. Electric motors hold value, but used batteries have essentially zero resale value because buyers can’t verify their charge history.

The bottom line: For casual flyers (two to three sessions monthly), electric wins economically. For weekend warriors logging ten flights every Saturday, gas becomes competitive over a three to five-year horizon.

Weather, Seasons, and Practical Flying Considerations

Environmental factors affect each system’s usability in ways beginners rarely anticipate.

Cold weather hits electric systems hard. Below 40°F, LiPo chemistry slows down—internal resistance spikes and voltage sags earlier. A battery delivering eight minutes at 70°F might only give you five minutes at 30°F. Flight performance drops noticeably. Smart electric pilots keep batteries in their car or jacket pockets until the moment they plug them in.

Gas engines love cold air. Denser air contains more oxygen molecules, so combustion is more efficient and power output actually increases. The challenge is starting—fuel doesn’t vaporize well when cold, so you need to richen the carburetor needles temporarily. Once running, though, gas systems excel in winter conditions.

Hot weather presents opposite challenges. Electric motors can demagnetize if they exceed their thermal limits. Electronic Speed Controllers hit thermal shutdown protection, cutting power unexpectedly. Batteries swell in extreme heat and can be permanently damaged. Gas engines risk vapor lock when ambient temperatures cause fuel to boil in the carburetor.

Wind handling reveals another key difference. Electric trainers are typically light foam construction with low wing loading—maybe 14 ounces per square foot. In winds above 10 to 12 mph, they get tossed around significantly. You spend the entire flight fighting turbulence rather than practicing maneuvers.

Gas trainers have higher wing loading—20 to 28 ounces per square foot—thanks to balsa construction and that heavy engine up front. They possess greater momentum, allowing them to punch through turbulence and track straighter. A beginner can comfortably fly a gas trainer in 15 mph winds where an electric would be grounded.

Field Etiquette and Community Considerations

Your power choice affects where you can fly and how you interact with the RC community.

Many flying fields now have noise restrictions. Urban and suburban sites often implement “electric only” hours before 10 AM or on Sundays. Some parks allow only electric planes entirely. Gas engines, even with good mufflers, generate substantial noise. This may limit your flying opportunities depending on local field access.

The community dynamic differs too. Gas fliers form tight mentorship networks because you need experienced help—someone to hold the tail during starting, someone to teach you carburetor tuning, someone to diagnose that weird sound the engine makes. This forced socialization accelerates your integration into the club culture.

Electric pilots have more autonomy. You can arrive, fly, and leave without speaking to anyone. While efficient, this isolation can be detrimental to learning. You might miss critical advice about setup or aerodynamics because you never had to ask for help.

Most AMA-chartered clubs support both power systems and provide the best learning environment. But some clubs lean heavily toward one camp or the other. Visit multiple fields in your area before committing. Ask about beginner support programs, instructor availability, and whether they have charging stations (for electric) or communal fuel supplies (for gas). The people matter more than the power source—a welcoming club with knowledgeable mentors will accelerate your progress with either system.

Making Your Decision: A Step-by-Step Framework

Let’s move from theory to your actual choice. Work through these assessment questions honestly:

Step 1: Assess Your Time Availability

Can you commit 30 to 45 minutes minimum per session, or do you have only 15 to 20 minute windows? This isn’t about patience—it’s about your actual schedule. If you’re squeezing flying into lunch breaks, electric’s quick turnaround makes sense. If you have Saturday mornings free, gas’s longer preparation ritual becomes manageable.

Step 2: Consider Your Learning Style

Do you prefer immediate feedback and rapid iteration, or do you enjoy systematic procedures and developing mechanical understanding? Neither personality type is superior, but they align with different power systems. If you read the manual cover-to-cover before assembling furniture, you’ll probably enjoy gas. If you prefer to figure things out by doing them repeatedly, electric suits that approach.

Step 3: Evaluate Your Budget Honestly

Can you handle $800 to $1,200 upfront, or do you need to minimize initial investment? Remember that electric’s lower entry cost comes with ongoing battery replacement expenses. If you plan to fly frequently, gas may cost less over five years. If you’re unsure about commitment to the hobby, electric’s lower barrier makes sense.

Step 4: Check Your Flying Location Options

Research actual fields within reasonable driving distance. Call ahead or visit to ask about power system restrictions. Are there electric-only hours? Do they have noise ordinances that limit gas engine operation? AMA clubs typically support both systems, but verify before purchasing equipment.

Step 5: Assess Your Mechanical Interest

Be brutally honest: does engine maintenance and tuning sound interesting or tedious? There’s no wrong answer here. If you want maximum flight time with minimum wrenching, electric delivers. If you’re fascinated by how engines work and enjoy troubleshooting, gas provides that satisfaction.

Step 6: Think About Your Growth Path

Where do you see yourself in two years? If you’re dreaming of giant-scale P-51 Mustangs or quarter-scale warbirds, gas is the natural path—those big scale models need the power and sound of gasoline engines. If you’re interested in 3D aerobatics in your local park, electric’s instant torque and quiet operation are advantages. For IMAC pattern flying, either works.

Choose electric if: You have limited space, fly near noise-sensitive areas, want plug-and-play convenience, prefer rapid learning through repetition, or are uncertain about long-term commitment.

Choose gas if: You have workshop space, belong to a club without noise restrictions, have access to experienced mentors, enjoy mechanical work, plan to fly larger scale aircraft eventually, or will fly frequently enough that lower operating costs matter.

Many experienced pilots eventually own both types. Starting with one system doesn’t lock you in forever—switching later is completely normal as your interests evolve.

Your First Purchase: Specific Recommendations

Let’s get specific about what to actually buy.

For electric, I recommend the E-flite Apprentice STS 1.5m as your trainer. The STS includes SAFE technology—Sensor Assisted Flight Envelope—which prevents you from banking past 60 degrees and provides a panic button that levels the wings when you release the sticks. This safety net dramatically reduces crash rates during the critical first ten flights. Expect to pay around $300 ready-to-fly.

For charging, get the Spektrum Smart S155 charger. It reads a microchip in compatible Smart batteries and automatically sets charge parameters, eliminating the risk of fires from incorrect settings. Buy three 3S 3200mAh 30C LiPo batteries—this capacity gives you eight to ten minutes of flight time, and having three packs lets you fly multiple times per session.

If you want to start even smaller, consider the HobbyZone Sport Cub S 2. This remarkable trainer weighs under 250 grams, exempting it from FAA registration and Remote ID requirements. You can legally fly it in small parks. It’s affordable ($150 range) and surprisingly capable.

For gas, the Hangar 9 Alpha 40 represents the gold standard trainer. The high-wing design provides self-righting stability, and the boxy fuselage is easy to repair after the inevitable hard landings. Pair it with a DLE 20RA engine—20cc displacement with rear exhaust. This engine fits airframes designed for older glow engines, parts are readily available, and the rear exhaust simplifies cowl installation.

You’ll need support equipment: a Sullivan Hi-Tork 12-volt electric starter for safe starting (no hand-flipping until you’re experienced), a fuel pump, a five-gallon fuel jug, basic screwdrivers for carburetor adjustment, and Tygon fuel line. Budget $150 for this support gear.

One critical point about transmitters: regardless of power system, invest in a quality 2.4GHz radio. Budget systems from Spektrum, Futaba, or FlySky all work well for beginners. Radio quality matters more than power system—don’t skimp here.

Avoid false economy on the airplane itself. The absolute cheapest options usually lead to frustration when parts break and replacements aren’t available. Stick with established brands that have parts support.

Realistic all-in budgets: $400 to $500 for electric, $600 to $750 for gas, including all accessories and support equipment needed for actual flying.

Common Beginner Mistakes to Avoid

Let me share the most frequent errors I see newcomers make.

Electric-Specific Mistakes:

- Underbuying battery capacity is the top electric error. Buy at least three packs, not one or two. You’ll want to fly multiple times per session, and batteries need cool-down time between uses. Also, one battery’s bad day shouldn’t ground you.

- Flying batteries below safe voltage causes permanent damage. Your Electronic Speed Controller has Low Voltage Cutoff protection, but some pilots ignore the warning beeps and fly until the motor cuts out. Once a LiPo cell drops below 3.0 volts per cell, internal resistance spikes and it becomes a fire hazard. Always fly to a timer or use telemetry to track voltage.

- The “C” rating confusion gets many beginners. That “50C” marking on your battery means it can safely discharge at 50 times its capacity. A 2200mAh 50C battery can deliver 110 amps continuously. Cheap batteries with low C ratings (20C or less) in high-performance planes will overheat, puff, and fail.

Gas-Specific Mistakes:

- Improper fuel mixing ratios destroy engines fast. Two-stroke engines need oil mixed with gasoline—typically 40:1 to 50:1 ratio. Too much oil causes plug fouling and excessive smoke. Too little oil causes piston seizure. Use a measuring cup and follow the manufacturer’s specifications exactly.

- Skipping break-in procedures is expensive. New gas engines need gradual break-in over several tankfuls of fuel with slightly rich settings. Run it hard immediately and you’ll score the cylinder, requiring a rebuild.

- The “lean run” mistake kills engines. Beginners often tune the carburetor for maximum RPM on the ground, thinking this is optimal. In flight, the engine unloads and runs even leaner, causing overheating and seizure. Always tune for peak RPM, then richen the needle by one-eighth turn.

Universal Mistakes:

- Choosing planes based on appearance is the number one error. That scale P-51 Mustang looks amazing, but it has difficult stall characteristics, narrow landing gear prone to ground loops, and is wholly inappropriate for a first plane. Start with a high-wing trainer. Always.

- Flying alone as a complete beginner is asking for trouble. Even experienced pilots benefit from a spotter. Find a club or at least recruit a friend to watch your first several sessions.

- Not joining a club or finding a mentor extends your learning curve unnecessarily. The membership fees for an AMA-chartered club ($50 to $100 annually) buy you access to experienced instructors, insurance, and a prepared flying field. The return on investment is enormous.

The Learning Timeline: What to Expect

Let’s set realistic expectations for your progression.

- Month 1: Electric pilots typically achieve basic circuits and controlled landings within two to three weekends. You’ll be flying rectangular patterns, making coordinated turns, and landing in a designated area. Gas pilots spend more time mastering engine operation and may have fewer total flight hours, but they’re building mechanical confidence alongside flying skills.

- Months 2-3: Electric pilots begin attempting basic aerobatics—loops, rolls, inverted flight. You can fly in moderate winds with confidence. Gas pilots achieve consistent starting and develop smoother throttle management. Your engine tuning skills improve, and dead-stick anxiety decreases as reliability builds.

- Months 4-6: Regardless of power system, you’re now a confident solo pilot. You understand trim adjustments, can handle mild emergencies, and your landings are consistent. The plateau that every beginner hits around month three or four starts resolving itself through refinement work.

These timelines assume regular flying—weekly sessions minimum. Fly only once a month and everything extends proportionally. Some people progress faster, others slower. This doesn’t indicate natural aptitude as much as it reflects available practice time and prior similar skills.

Here’s the encouraging part: by the six-month mark, the initial power system choice matters less than the quality of your practice. Electric pilots are eyeing larger, heavier planes (possibly gas). Gas pilots are comfortable with mechanics and ready to expand their fleet. Both paths lead to the same destination—confident, capable pilots who can fly diverse aircraft. The journey just feels different along the way.

Conclusion: There’s No Wrong Choice

Both electric and gas power systems will successfully teach you to fly RC planes. The “best” choice depends entirely on your situation, learning style, and goals—not on any inherent superiority of one system over the other.

Many experienced pilots own and enjoy both types. Electric for quick afternoon sessions at the park. Gas for long Saturday mornings at the club field. The systems complement each other rather than compete.

Your next step is simple: visit a local flying field. Watch both power systems in action. Talk to actual pilots rather than relying solely on internet forums. Ask about instructor availability, beginner programs, and what they recommend for someone just starting. Trust your instincts about what appeals to you.

The fact that you’re reading this guide and thinking carefully about your choice already puts you ahead of many beginners who rush in without research. You’re approaching this methodically, and that mindset predicts success regardless of which power system you choose.

Whether you select electric or gas, you’re about to join a welcoming community of pilots who share your enthusiasm for RC flight. The fundamentals of flying are the same—understanding lift, managing energy, reading the wind. The power system is just the tool that gets you airborne.

The sky is waiting. Now go choose your path to it.

Key Takeaways

- Electric power offers lower entry costs ($400-600), faster learning through high-repetition sessions, and minimal maintenance, but requires battery management and faces limitations in cold weather and wind.

- Gas power demands higher initial investment ($800-1,200) and mechanical learning but provides longer flight times, better wind penetration, and teaches disciplined energy management.

- Your choice should match your lifestyle constraints—available time, mechanical interest, and flying location access—rather than focusing solely on cost or technology preferences.

- Both systems successfully develop competent pilots; the learning journey simply emphasizes different skill sets along the way.