Bell P-39 Airacobra History

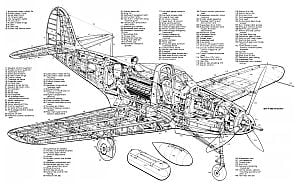

One of the first interceptors to have a tricycle undercarriage, the Bell P-39 Airacobra was unique in having its 1,150 hp Allison V-1710-E4 engine mounted behind the pilot, the propeller being driven via a long extension shaft.

Originating as the Bell Model 12, the Airacobra was designed by Robert J. Woods primarily as a vehicle for a heavy-caliber cannon. The XP-39 flew for the first time on 6 April 1938, a contract for thirteen YP-39 test aircraft being awarded in April 1939. These were based on the prototype, after its modification to XP-39B standard without the engine supercharger originally fitted.

The first Bell P-39 Airacobra production version was the P-39C, but only twenty of these were completed. In the P-39D, the 37 mm cannon and twin 0.50 in guns in the nose were supplemented by 0.30 in wing-mounted machine-guns and provision was made for an external bomb or fuel tank to be carried. Four hundred and four P-39Ds were built for the US Army, delivery beginning in April 1941. A further four hundred and ninety-four P-39D-1 and D-2 Airacobras (Bell Model 14) were built for Lend-Lease allocations, these having a nose cannon of lighter (20 mm) caliber.

Airacrobras were initially ordered by France, but after the armistice, the contract was taken over by Britain. Following Air Fighting Development Unit trials, one squadron, No 601, was re-equipped with the type. It was found that performance at altitude was very poor and mechanical unreliability led to serious serviceability problems. The Bell P-39 Airacobra was briefly used for ground strafing but was withdrawn from operations after four months. The bulk of the 670 ordered were canceled and instead went to the US Army Air Corps, while many were supplied to Russia, where they proved suitable for low-level attacks.

Numerous Bell P-39 Airacobra variants appeared, the difference between which principally concerned the variant of V-1710 engine and type of propeller fitted; they included the P-39F, J, K, L, M, N and Q. The Last of these introduced a change of armament, replacing the four 0.30 in wing guns by two of 0.50 in caliber. The two most widely built models were the P-39N (two thousand and ninety-five) and the P-39Q (four thousand nine hundred and five).

The entire production of the Bell P-39 Airacobra, ending in 1944, was undertaken by Bell, who built a total, including experimental machines, of nine thousand five hundred and fifty-eight. Well over half this total, mostly P-39Ns and P-39Qs were allocated to the Soviet Union; nearly two hundred of these were lost en route, but four thousand seven hundred and fifty-eight arrived safely to render excellent service on the Eastern Front between 1942 and 1945.

| Specifications |

|---|

| Aircraft Type: |

| fighter |

| Dimensions: |

| wingspan: 34 ft |

| length: 30 ft, 2 in |

| height: 12 ft, 5 in |

| Weights: |

| empty: 5,462 lb |

| gross: 7,651 lb |

| Power plant: |

| 1 × 1,200 hp Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled engine |

| Performance: |

| maximum speed: 382 mph |

| ceiling: 35,000 ft |

| maximum range: 650 mi |

| Armament: |

| 2 × 0.50 in caliber nose guns |

| 4 × 0.30 in mm wing guns |

| 1 × 37 mm caliber cannon |

| Service dates: |

| 1939–1944 |

Operational History

The Pacific

The 31st Pursuit Group was the first operational unit to receive the P-39 Airacobra. Flying with the Blue Forces” of the First Army in the September-November 1941 “Carolina Manoeuvres”, the 31st, together with the U.S.A.A.C. units, first tested techniques and procedures which stood them in good stead in the early years of actual warfare. Most notable of these was the first test at Marston, North Carolina, of the pierced metal “Marston Mat” runway.

The 8th Pursuit Group was the first to take the P-39 into combat. After Group Headquarters was established in Brisbane, Australia on March 6, 1942, detachments were sent to forward bases in New Guinea. In July the 8th was joined by the squadrons of the 35th Fighter Group: originally attached to the 31st F.G., the 39th, 40th and 41st Fighter Squadrons were transferred to the 35th F.G. and as such went into action in New Guinea.

The 347th Fighter Group initially received 46 aircraft carrying British serials in the BW108 to BW183 range, and retaining the original British upper surface camouflage of dark earth and dark green (see “European Operations” below). Assembled from crates along with the U.S. contract P-39D-1s fitted with 20 mm. cannon to match, the unit began training at Tontouta Air Base on New Caledonia. Aircraft of the 67th Fighter Squadron, led by Capt. D. D. Brannon, flew the 350 miles over water to Guadalcanal on August 22, 1942. The squadron’s first victory was scored the following day when Capt. Brannon and his wingman Lt. Fincher shared a Zero kill between them.

Early flights showed a lack of maneuverability, but the real need at the time was for dive-bombing capability and in this rôle, the P-39 was well regarded. In addition to full standard armament, a bomb of 100, 350 or 500 lb. weight could be carried. In a 347th F.G. combat report dated November 13, 1942, 1st Lt. Wallace L. Dinn reported: “The P-39D-2 type plane is a splendid attack plane.” Since the accuracy and success of any diving attack was proportional to the enthusiasm of the pilot, this resulted in some low pull-outs. After securing a 500 lb. bomb hit on a Japanese cruiser, Lt. J. J. Jacobson registered a pull-out altitude of —40 feet! Altimeter checking after his return to Henderson Field indicated an 80 ft. error, the true pull-out altitude thus being 40 ft. above the ocean. Lt. Dinn felt that the P-39 would have been a good altitude fighter if it had a two-speed blower and four free-firing -50 cal. wing guns. Late P-39Q versions were fitted with two 50 cal. guns in underwing fairings in place of the four -30 caliber weapons. Luckily, the usual circumstances of combat over Guadalcanal were contacts with enemy aircraft covering task forces and thus normally occurred below 10,000 ft.

The tricycle gear enabled the P-39 to operate from extremely rugged airstrips. During the time spent on New Caledonia, one flight operated P-400s from a 2,800 ft. widened dirt road without any difficulty whatsoever. This ability came in useful during operations on the “Canal”. With a no-flap stall at 105 m.p.h., approaches were made flat and fast until Japanese rifle fire forced them up. The resulting steep approach, accompanied by a full-flap, gear-down sideslip into the strip while under continual fire from enemy positions led to some thrilling landings!

Unless the engine was hit and the Prestone coolant lost, the P-39 held together through anything. During a night landing, Lt. Martin C. Haedtler of the 67th Squadron hit three bales of steel landing mats in a crash that removed the right main gear, the right-wing, the prop, and the gearbox; the cannon was bent into a hook that proved useful when it came to towing the Airacobra off the runway. Other than a stretched neck from the abrupt stop, Haedtler’s only injuries were aches and bruises.

The aircraft was very stable and flew with little maintenance. Combat experience showed that it could operate with little more than an airspeed indicator and gearbox pressure gauge intact. The controls became stiff during high-speed dives, and later models had servo aileron boost to counteract this tendency.

During the 67th Fighter Squadron’s training, the dive speeds with 100 lb. water-filled practice bombs reached 600 m.p.h. I.A.S. Whether this was due to Mach error in the system is not known, manuals recommended a maximum dive speed of 475 m.p.h. L.A.S.

As newer aircraft types came into service the P-39s were gradually withdrawn from combat. The 347th F.G. was the last Pacific-based unit to give up the Airacobra, finally converting to P-38 Lightnings in August 1944. (The last unit in the European Theatre was the 332nd F.G., which employed the type in operations in Northern Italy until late 1944.)

North To Alaska…

While hardly typical of most operations, the experiences of the 54th Fighter Group are fairly indicative of the early war situation.

Lt. Leslie Spoonts of Fort Worth, Texas, graduated from flight training on December 12, 1941, just five days after the Day of Infamy”, and joined the 54th Group late in January 1942. Assigned to the 57th Squadron, he came under the command of L. F. Stetson at Paine Field, Washington. A veteran of 15 years’ commissioned service as a pilot, Stetson was still only a First Lieutenant; and promotions were not the only commodities in short supply at that time. While the Group was well supplied with pilots, mostly former class-mates, it had not a single operational combat aircraft. In addition to a Stearman or two and an AT-6 or BC-1 used for gaining flight time, each squadron had about three old P-40s, none of which were airworthy. After a few weeks, each squadron received one brand-new P-39 direct from the factory; all pilots were checked out and got in a couple of hours of flight time.

Bad weather in Washington state forced a move to Harding Field, Louisiana, where the Group underwent considerable training; one rarity in the program was aerial gunnery, by no means standard training at that time. In early May, informed of an imminent “maneuver”, the unit prepared to move on once more.

In what was to be the first instance of the complete operational deployment of a unit by air, the pilots of the 42nd Squadron flew their aircraft to Alaska to reinforce the 28th Composite Group; the 56th Squadron flew to Santa Ana and the 57th to San Diego, taking up patrol duties on their portions of the Californian coast. The Group’s ground personnel were deployed to their various locations by airline-piloted C-47s. Later named the 28th Bombardment Group, the 28th Composite operated P-38s, P-40s, B-26s and LB-30s between 1941 and 1943. It had been reported that some of the 54th’s “broken” P-39s were repaired and flown after being left behind.

After the Japanese attack on Dutch Harbour, Alaska, on June 4 the remaining squadrons of the 54th Fighter Group flew up as additional reinforcements. The headquarters of the 42nd Squadron were at Kodiak while the pilots operated from Adak Island; on June 21 the 57th moved into Kodiak and the 56th went to Nome. Procedure was for the 42nd to remain at Adak while pilots were rotated into it for combat duty.

In the course of their brief foray into history, the 54th Group encountered numerous Japanese types, all of which were simply reported as “Zeros”. There were some well-known names in the Group; a replacement pilot who joined the 56th Squadron was one Thomas B. McGuire, and Gerald R. Johnson was with the 57th. Both were later to gain fame in the Philippine-based 49th Fighter Group, scoring 38 and 22 kills respectively. One of their mates in both the 54th and 49th Groups was Wallace R. Jordan, who scored six kills; and the 45th’s Group Executive Officer was Major (later Brigadier-General) Charles M. McCorkle who was to command the 31st Fighter Group in Africa and end the war with 11 victories.

Operations in the Aleutian Islands were extremely rugged, and the Airacobra’s tricycle undercarriage was most useful. At Adak, it was quite common to encounter a 30 m.p.h. cross-wind at 90° to the runway; it never blew parallel to the strip. Under winter conditions the P-39 was a breezy airplane, there being no engine in front to heat the air that filtered into the cockpit. The situation was not aided by the fact that the aircraft heaters had been disabled; they operated from the fuel system and were rumored to thin the mixture and damage the engine. Numerous ingenious methods were employed to solve the problem. Everything that could be taped over was taped over, including the left-hand door. (The P-39 was almost unique in being a “right-hand” type, with handholds on the starboard side.) Lt. Spoonts “acquired” unused canvas summer tent caps and covered the gun ports in the cowl by placing the canvas under the cover plate and trimming the excess; these could be shot through if necessary. Many pilots stuffed newspaper into the legs of their flying suits for insulation.

During the operation against the Japanese at Kiska Island, the 54th Group’s total score was about 20 enemy aircraft for the loss of one pilot. The C.O. of the 42nd Squadron, Maj. Miller, was the only P-39 pilot to be shot down; due to fuel shortage, the other aircraft on the mission were forced to leave the area after he baled out into Kiska Harbour. The PBY rescue aircraft had already left the vicinity and it is not known if Maj. Miller was captured or if he survived the war.

The mixed armament of 37 mm. cannon and .30 and •50 caliber machine-guns resulted in sighting problems. While all could be bore-sighted for a specific impact point at a given range, the dissimilar trajectories caused bullet dispersion at other ranges. In an attempt to compensate for this effect early aircraft were fitted with “Christmas Tree” sights; horizontal lines across a vertical line indicated the various impact points.

Captain A. T. Rice was one 54th Group pilot who was not particularly bothered by this, on one mission at least. With all his other guns out of action, Rice destroyed two Japanese floatplanes (there was no airfield on Kiska) using only the 37 mm. gun. Four shots were fired at one target, two at the second. Only two shells hit, but with high explosive 37 mm. ammunition one hit was more than enough; but considering the “Roman Candle” rate of fire of the weapon, Capt. Rice’s marksmanship is impressive.

Having been attached to the 11th Air Force on temporary duty (TDY) pilots of the 54th Fighter Group began their trip to the United States, in small groups of six or eight aircraft, at the beginning of January 1943.

European And Foreign Service

The first foreign order for Airacobras had come in the shape of a $9,000,000 French contract for 200 aircraft. Two million dollars of this sum was in cash, most welcome at a time when although large orders had been received, the expansion required to fulfill them was putting a strain on Bell Aircraft’s budget.

France’s fall under the onslaught of the German Blitzkrieg prevented any of these aircraft being delivered, but eventually, French pilots were to receive nearly the same total of 200 machines. The first Free French unit to receive the type was G.C.III/6 “Roussillon”, which began to equip with P-39Ns in April 1943. N and Q models also served with at least three other French units before the end of the war; these were G.C.1/4 “Navarre”, G.C.1/5 “Champagne”, G.C.III/5 “Ardennes” and probably G.C.II/3 “Dauphine” also. Disbanded during the Vichy period, G.C.II/6 “Travail” was reformed with P-39s in July/August 1944. Remaining in French service as late as 1947, P-39s flew coastal patrols in the North African theatre in 1943, and ground attack missions in Southern France and Italy during the last two years of the European war.

The British took on the lapsed French order for 200 machines and in all ordered 675 Bell Model 14s, under the name “Caribou”. Renamed Airacobra I, they reached only one Royal Air Force squadron No. 601 “County of London” Sqn. Having converted from the faithful and popular Hurricane, the pilots were expecting a really up-to-date aircraft as a replacement; and their first disappointment came when, having received 11 aircraft by the end of September 1941, they discovered the top speed to be 30 m.p.h. less than they had been led to believe.

At this time the Air Fighting Development Unit were operating from the same airfield as No. 601 Sqn., namely Duxford; and the squadron pilots had ample opportunity to test their new mounts against other contemporary types including captured German Messerschmitt Bf 109Es and Fs as well as the twin-engined Bf 110. In climb tests, the Airacobras were left standing by Hurricanes, Spitfires and Bf 109s and also by the then-new Typhoon. Above 15,000 ft. they all flew rings around the P-39.

The small high-pressure tires caused difficulties during operations from the usual R.A.F. grass airstrips; dirt and debris tended to clog the electrically-operated landing gear and flaps. Unfamiliarity with tricycle undercarriages led to long landing runs and consequent overheating and brake failures. American practice was to ignore the tricycle undercarriage and land in a normal tail-low attitude, holding off until the nose wheel touched of its own accord; brakes were applied only then. Other problems occurred during firing trials; quantities of gun gas filled the cockpit and at times reached lethal concentrations. During night trials the pilots were blinded by muzzle flashes; doubly dangerous when the aircraft were committed to collision courses. American aircraft were often fitted with flash-hiders for cannon and cowl guns.

The only R.A.F. Airacobra operation was on October 9, 1941, when four aircraft left Duxford and strafed barges on the French coast after refueling at Manston.

In a foretaste of the P-39s most widespread use, a group of Russian pilots were taken to Duxford and flew No. 601’s aircraft. After the squadron moved to a base near the city of York, two British pilots were killed due to their aircraft entering uncontrollable flat spins. Although a pleasant plane to fly, it required trim adjustment during differing flight regimes to compensate for the use of ammunition and fuel and the aft movement of the center of gravity; aerobatics were prohibited in tail-heavy aircraft. After the above-mentioned crashes whatever little pilot confidence remained vanished completely, and No. 601 gratefully re-equipped with Spitfires.

Of the 675 machines ordered, 212 which reached England were sent on to Russia, the first of a total of 4,747, more than half the entire production of the P-39. Highly regarded by the Russians for its ground attack capability, the P-39 was nicknamed “Little Shaver”; “shaving” was the current Soviet Air Force slang for ground-strafing. The first batch was followed by a large proportion of the P39-N and P-390 production runs.

Of the 179 British-ordered aircraft retained in the United States for U.S.A.A.C. service and redesignated P-400, many were sent to Australia and New Caledonia. Operating in mixed units with P-39Ds, they bore the early weight of the Japanese advances, supporting the Australian ground forces in New Guinea and the epic American struggle for Guadalcanal.

The next, though hardly successful European operation came when the 31st Fighter Group, re-formed with the 307th, 308th and 309th Squadrons, began operating from England. With headquarters established at Atcham, the 31st conducted one combat operation against Hitler’s Europe. Twelve aircraft took part; six returned. The Group re-equipped with Spitfires.

When World War II descended upon Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, the United States, in the words of Major Alexander P. Seversky, “did not have a combat aircraft worthy of the name.” A harsh judgment; but the P-39 and P-40 were the only halfway-modern fighter types operational with the Army Air Corps. Together with the Navy’s Grum man Wildcat, they bore the brunt of the early fighting in the Pacific. They were not the best in the world; some probably considered them a little less than nothing, but they were all there were to be had. The Japanese considered the P-39 a hard aircraft to shoot down; but that is hardly a compliment, either. All in all, the career of the P-39 could be summed up like this: it bought enough time for the full might of the United States to be geared for war with the spirit of its defiant pilots in the face of overwhelming odds, its tough hide.

I like the potential of the Russian Cobra. Some even had a trio of B-20s in the nose, a bubble top, a turbo, and larger 223 SF wing for the same span! [P-45D]

Even the VYa-23 cannon and UBS gun was used as well as the 20mm ShVAK and M2 Hispano, on various Cobras. The P-39 still held the advantage over the P-45 at low level.

They addressed the weaknesses of the P-39, before the P-63.

This version had the same 386 mph speed but up at 21.000′!

Climb to 20,000′ took 6.3 min.

It was heavier at 7900 lbs loaded, but had 1375 hp.[P-45A]

9 VVS regiments reportedly flew it. So did select US units.